Beneath Fire Island’s serene beauty and picturesque barrier beaches lies a haunting maritime history. The coastline has witnessed countless shipwrecks, each with its own story of heroism, tragedy, and the relentless power of the sea. From daring rescues to devastating losses, these wrecks serve as poignant reminders of the perils that once defined Long Island’s waters. (Luckily, locals built a lighthouse to help mitigate the problem of shipwrecks. Read about the Fire Island Lighthouse here.) Below are some of the most notable shipwrecks near Fire Island and the compelling histories they hold.

The Wreck of the Elizabeth (1850)

Details: The Elizabeth was one of the most publicized shipwrecks preceding the founding of the United States Lifesaving Service. This 530-ton vessel wrecked in a summer storm off what is now the Point O’Woods area on July 19, 1850. The ship was sailing from Italy, carrying a cargo that included marble, silks, oils, and soaps, along with five passengers and a crew of fourteen.

The tragedy became particularly memorable due to the high-profile passengers who perished, including Margaret Fuller, a noted author, scholar, and feminist. Fuller, celebrated among her literary peers such as Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, drowned alongside her husband and young son.

The ship’s captain had died of smallpox days before the wreck, leaving navigation to an inexperienced first mate. At 3:30 a.m., the ship struck a sandbar, causing its cargo of marble to breach the hull and flood the hold. Some passengers and crew swam to safety, while others, including Fuller, were lost as volunteer lifesavers attempted to throw lines to the ship.

The wreck was further marred by looting, with 40 individuals later convicted of stripping the ship of its valuable cargo. The public outcry over Fuller’s death, amplified by her literary peers, brought increased attention to the need for organized lifesaving efforts.

Source: National Park Service

The Louis V. Place (1895)

Among Fire Island’s most infamous shipwrecks is the tragic story of the Louis V. Place, a schooner laden with coal en route from Baltimore to New York. The vessel’s fateful journey ended in February 1895 when it became stranded on a sandbar east of the Lone Hill Life-Saving Station, encased in ice and battered by unforgiving winter storms.

Trouble began days before the wreck, as severe weather coated the sails, rigging, and hull in layers of ice, transforming the ship into what witnesses described as a “drifting iceberg.” By February 8, the schooner was helplessly stranded. Spotting the wreck, the Lone Hill lifesaving crew quickly summoned reinforcements from neighboring stations, but they were already stretched thin, responding to another shipwreck, the John B. Manning, just a mile away.

As rescuers gathered, conditions made launching a rescue boat impossible. Gale-force winds, icy waves, and the hypothermia-stricken crew of the Place created an insurmountable challenge. Despite firing a line from the Lyle gun to establish a breeches buoy system, the frozen, frostbitten crew lacked the strength to secure it.

Tragedy struck as Captain William Squires and cook Charlie Morrison fell from the rigging, where the crew had sought refuge from the freezing waters below. When daylight arrived, rescuers discovered that only two of the eight crew members were still alive. After nearly 40 grueling hours, lifesavers finally launched a rescue boat and brought the survivors to safety.

The wreck claimed six lives, leaving only one survivor from the two rescued sailors. In their memory, eight plots were prepared at Patchogue’s Lakeview Cemetery, though only four bodies—those of Gustave Jaiby, Charles Allen, August Olson, and Fritz Oscar Ward—were ever recovered and buried. The story of the Louis V. Place endures as a somber reminder of the relentless danger faced by mariners along Fire Island’s shores.

Source: National Park Service

The Bessie A. White (1922)

The wreckage of the Bessie A. White, a four-masted Canadian schooner, has periodically emerged from the sands of Fire Island, uncovered by Superstorm Sandy east of Davis Park. Thought to be over 90 years old, the ship was carrying a cargo of coal when it met its tragic fate. The remains of the schooner have previously been exposed by severe weather events, including the North American Blizzard of 2005 and a nor’easter in the mid-1980s.

The Bessie A. White, over 200 feet long and displacing 2,000 tons, departed Newport News, Virginia, in February 1922, bound for St. John’s, Newfoundland, with 950 tons of soft coal. On February 6, thick fog and darkness caused the vessel to run aground half a mile west of Smith Point. The grounding ruptured her seams, flooding the ship with up to 10 feet of water. Remarkably, all crew members, along with the ship’s cat, survived the ordeal.

Source: The Old Salt Blog

The SS Savannah (1821)

In October 2022, a weathered piece of shipwreck debris washed ashore on Fire Island following Tropical Storm Ian, capturing the attention of maritime historians. Believed to be part of the SS Savannah, the first vessel to cross the Atlantic Ocean using steam power, the wreck dates back to 1821, when the ship ran aground and broke apart off Fire Island’s coast.

The 13-foot section of the wreckage is currently held by the Fire Island Lighthouse Preservation Society, which is collaborating with the National Park Service to confirm its origins and prepare it for public display. While identifying the piece with complete certainty may be challenging, experts consider the Savannah a strong candidate among the island’s historical shipwrecks.

Source: CBS News

The Wreck of the Prince Maurice (1657)

On March 13, 1657, the Prince Maurice, a ship owned by the Dutch West India Company, was blown off course during a nor’easter and wrecked along the uncharted barrier beach now known as Fire Island. The ship carried 129 passengers, including Dutch soldiers, who faced severe challenges: starvation, freezing temperatures, and fear of retaliation from local Indigenous tribes.

The crew’s fears were not unfounded. A decade earlier, Dutch mercenaries had led violent campaigns against Long Island’s Indigenous peoples, leaving tensions high. Despite this history, members of the Unkechaug Nation discovered the stranded Dutch and chose to offer aid. Using dugout canoes, they rescued the crew, transported them to their village near what is now Carmans River, and provided shelter and food from their limited winter supplies.

The Dutch expressed their gratitude by trading linens and cloth, building trust between the groups. To secure their rescue, a crew member sent a letter to New Netherlands Director Peter Stuyvesant via an Indigenous messenger, who safely delivered it to a mediator in Manhattan. Stuyvesant then dispatched ships to retrieve the survivors.

Source: Fire Island & Great South Bay News

USS San Diego (1908)

The USS San Diego was a proud member of Theodore Roosevelt’s famed Great White Fleet, making her debut in 1904. Though she served with distinction, her fate was sealed on July 19, 1918, when an explosion, likely caused by a German mine, sent the ship to the ocean floor. Located 13 miles south of Fire Island Lighthouse, the wreck now rests upside down, a haunting reminder of her tragic end.

Source: Patch

Oregon (1886)

The Oregon was a 520-foot transatlantic passenger liner, built in 1881, that sank in March 1886 after colliding with the schooner Charles H. Morse near Fire Island, New York. Despite attempts to save the ship, the crew abandoned her two hours after the collision, with only one casualty among the 852 passengers. The wreck now lies in 125-130 feet of water, 21 miles southeast of Fire Island Inlet, in a region known as Wreck Valley. The Oregon’s steel hull has collapsed over time, leaving its engine and propeller exposed. Artifacts like portholes, silverware, and china have been recovered by divers. The site remains a popular dive spot due to its good visibility, fish, lobsters, and fascinating history, though the wreck has been heavily picked over by artifact hunters.

Source: Fire Island & Great South Bay News

Hylton Castle (1886)

On January 11, 1886, the Hylton Castle, a 251-foot-long ship, sank after being battered by a heavy gale while transporting corn from New York. The crew abandoned the ship in two lifeboats, with one reaching shore, while the other was rescued after drifting for three days. The wreck now lies 15 miles southeast of Fire Island Inlet at a depth of 100 feet.

Source: The Fisherman

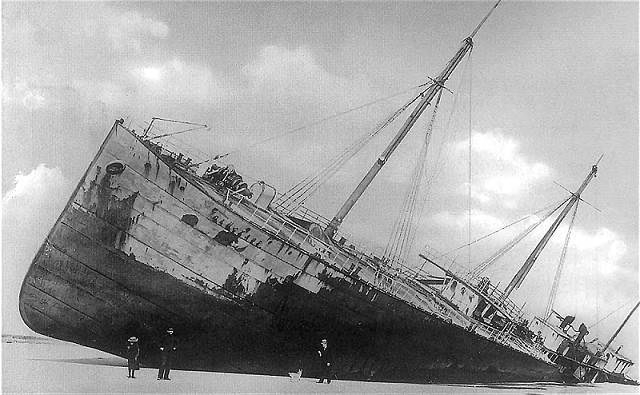

Gluckauf “The Wreck” (1893)

Date of Wreck: March 25, 1893 (dates may vary slightly). Offshore, near Blue Point Life Saving Station, Fire Island. The Gluckauf, a German-built tanker and the world’s first bulk oil carrier, ran aground during a storm while en route from Germany to New York. After multiple attempts to refloat the ship, it was abandoned. Over time, it became a tourist attraction, with visitors exploring the wreckage. However, by the early 1900s, most of the ship’s parts were stripped by junk dealers, and the wreck eventually sank into the sand, though the hull still remains visible at low tide. The Gluckauf is considered a historical relic of early oil tanker design and is a popular site for surfcasters, although the wreckage is now a jumbled mass of twisted iron. The wreck is now mostly buried beneath sand, though small sections are still exposed at low tide. The ship lies in 25 feet of water, around 75 to 100 feet offshore. “Gluckauf” means “good luck” in German, a name that contrasts with its fate.

Source: Multiple

Coimbra (1942)

The Coimbra rests in pieces 30 miles southeast of Moriches Inlet in 180 feet of water.

The British tanker SS Coimbra met its tragic end on January 15, 1942, when it was torpedoed by the German U-boat U-123 during World War II. The attack occurred 27 miles off Long Island’s Shinnecock Canal, as the ship was en route from Bayonne to Halifax. The explosion from the two torpedoes sent the tanker sinking rapidly, killing 30 of the 36 crew members. The ship’s wreckage remained a ghostly reminder, with oil leaks continuously rising to the surface for years.

In 2019, a major salvage operation led by the Coimbra Contract Corporation removed over 476,000 gallons of oil to prevent further environmental damage. Today, the wreck lies in three sections, home to an abundance of marine life, including sharks, cod, and bluefin tuna. Despite the oil cleanup, small leaks persist, keeping the memory of the Coimbra‘s tragic sinking alive in the waters off Fire Island.

Sources: Professional Mariner and NUMA.net

Kenosha (1909)

Originally built as the Madagascar in 1894, this ship changed its name to Kenosha in 1907. The vessel sank on July 24, 1909, after foundering in a storm while carrying coal. The wreck was misidentified as the “Fire Island Lightship” until 1986 when a diver discovered a brass windlass cover that revealed its true identity. The Kenosha now rests 10 miles southeast of Fire Island Inlet in 105 feet of water.

These shipwrecks are reminders of Fire Island’s rich maritime history and the dangers of the sea. Their stories continue to captivate historians, divers, and beachgoers alike.

Photo: German tanker Glückauf stranded on 23/24-3-1893 in heavy fog at Blue Point Beach at Fire Island. Tourists were common at the wreck site for years after. Benjamin T. West, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons