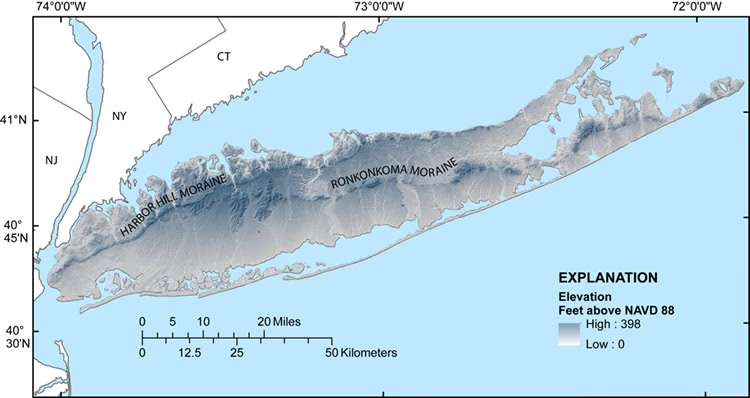

You’re standing on the leftovers of a 60,000-year-old glacier. Seriously. Long Island didn’t just show up one day with bagels and beach traffic. It was bulldozed into place by a mile-thick wall of ice, slammed with waves, and is still getting a makeover from Mother Nature. Here’s the bizarre, beautiful, and sandy story of how our fish-shaped island came to be.

Long Island’s Basement is Older Than Dinosaurs

-

Beneath all that suburban sprawl lies ancient metamorphic bedrock that’s over 400 million years old.

-

This rock—visible up in Manhattan and the Bronx—is mostly hidden on Long Island, buried under layers of sand, clay, and glacial debris.

-

That bedrock tilts downward to the south and east and doesn’t form any noticeable hills or ridges on the surface.

-

On top of it sits a wedge of Cretaceous-period sediments (yes, from the same time as the dinosaurs), made of sand, gravel, and clay.

-

This wedge is thickest under Fire Island, where it’s more than 2,000 feet deep, and thins out toward Queens and Long Island Sound.

Then Came the Glacier

-

Around 60,000 years ago, the Laurentide ice sheet—specifically its Wisconsin Glacier portion—crawled down from the north and began sculpting what would become Long Island.

-

As it retreated, it dumped piles of gravel, rock, and dirt, forming two major ridges known as terminal moraines.

-

These glacial leftovers shaped the island’s spine and its iconic fish-like silhouette.

-

Long Island has alternated between being an island and a peninsula over the centuries, depending on sea level and sediment deposits.

-

Fossils are rare here, mostly because glaciers are not known for being gentle with prehistoric remains.

After the Ice, the Ocean Took Over

-

Once the glacier melted, the coastline began to evolve—and never really stopped.

-

Waves, tides, and storms chewed away at glacial sediments and started sculpting sandy shorelines.

-

Streams and rivers carried more material toward the sea, slowly reshaping upland areas and building up coastal zones.

Long Island’s Edges Are Always on the Move

-

Nowhere is this post-glacial chaos more visible than the south shore.

-

The Ronkonkoma moraine, near Montauk Point, has taken a beating from Atlantic storms for thousands of years.

-

The South Fork has actually shrunk by several miles due to constant wave erosion.

-

As the moraine erodes, currents push the sand and gravel westward—creating barrier beaches like Fire Island, Jones Beach, and Long Beach.

-

These beaches are built by wave action and currents, often forming offshore bars that drift west and grow over time.

-

Since Fire Island Lighthouse was built in 1844, the island has expanded five miles to the west.

Dunes, Grass, and Grit

-

Wind-blown sand forms dunes further inland, where beach grasses and shrubs help hold the sand in place.

-

These vegetated dunes act as natural armor, reducing storm damage and keeping the beaches from washing away.

Where the Water Gets In: Inlets and Lagoons

-

Barrier beaches are interrupted by inlets—natural channels that allow tides to flow in and out of the bays behind them.

-

Over time, marshes fill in behind the beaches, slowly connecting them to the mainland.

-

Behind Long Beach, you can still see this silting process in action, with narrow channels dividing marshy islands.

Drainage: The Island’s Subtle Stream Game

-

Long Island’s small size and elevation mean it doesn’t have major rivers—just lots of short streams and brooks.

-

Most freshwater runoff flows straight to the sea without forming big rivers.

-

The largest river is the Peconic, which runs east to west, unlike most others on the island.

-

Other notable rivers like the Carmans, Connetquot, and Nissequogue appear bigger than they are due to their estuaries—flooded valleys where freshwater mixes with salty seawater.

A Low Island with High Stakes

-

Long Island’s highest point is Jayne’s Hill in Suffolk County—soaring to a dramatic 401 feet above sea level.

-

With such a low profile, Long Island is vulnerable to flooding and rising sea levels. In the distant future, parts of it could be underwater.

Yes, We Get Earthquakes

-

While we’re not exactly on the San Andreas fault, Long Island has had its share of minor earthquakes. They’re usually small but still enough to rattle the dishes.

-

For a list of historical quakes, check out the earthquake archives. You might be surprised how often the ground has shaken under your feet.

Photo: United States Geological Survey (USGS), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.